It should be initially disclaimed that the Sullivan of the Sullivan Loft does not refer to the renowned American architect, Louis, who famously uttered ‘form ever follows function’ but rather the client. A bachelor working in finance, this Sullivan may be more inclined to agree with Stewart Brand’s rephrasing ‘form follows funding’. And yet, for more reasons than surname similarity, it’s worth entertaining both aphoristic arrangements in describing this space in Boston’s Seaport.

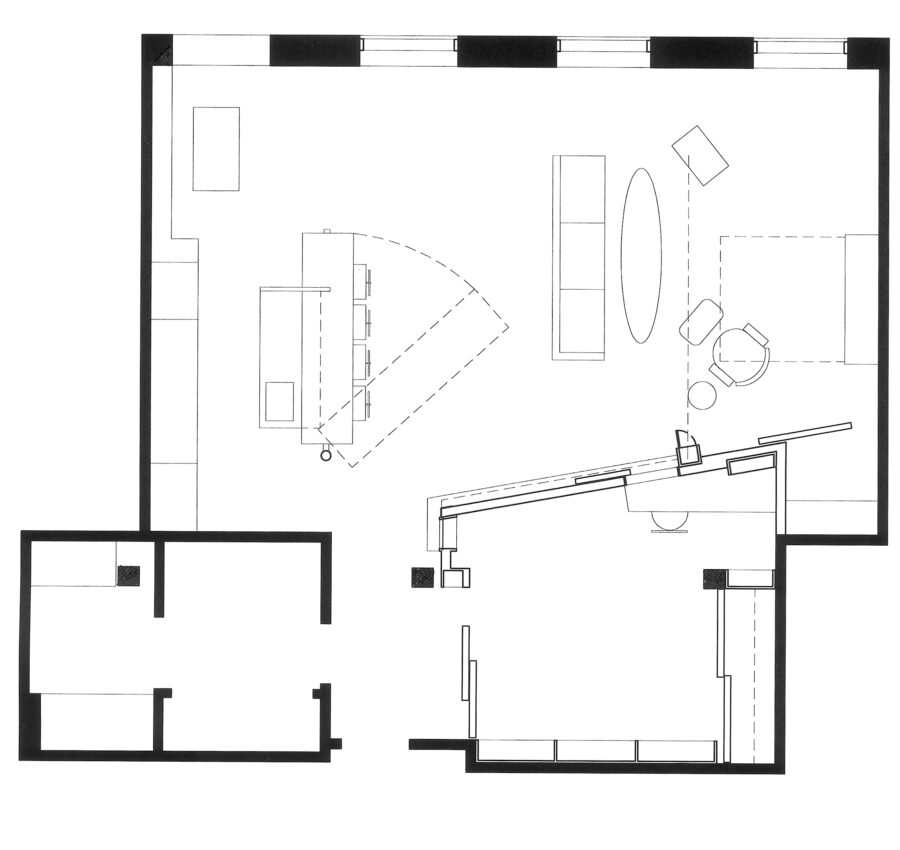

First-off function, as the space is located within a factory turned into residential units. The result is a deep unit plan in which only one wall receives daylight. Considering funding, the desirable downtown location of the building means that the unit’s unevenly-illuminated footprint is also a limited-yet-pricey one. This financial fact leads back to function, as the client’s demands were that all typical household activities – living, dining, cooking, sleeping, working, etc. – still be accommodated within the small square footage.

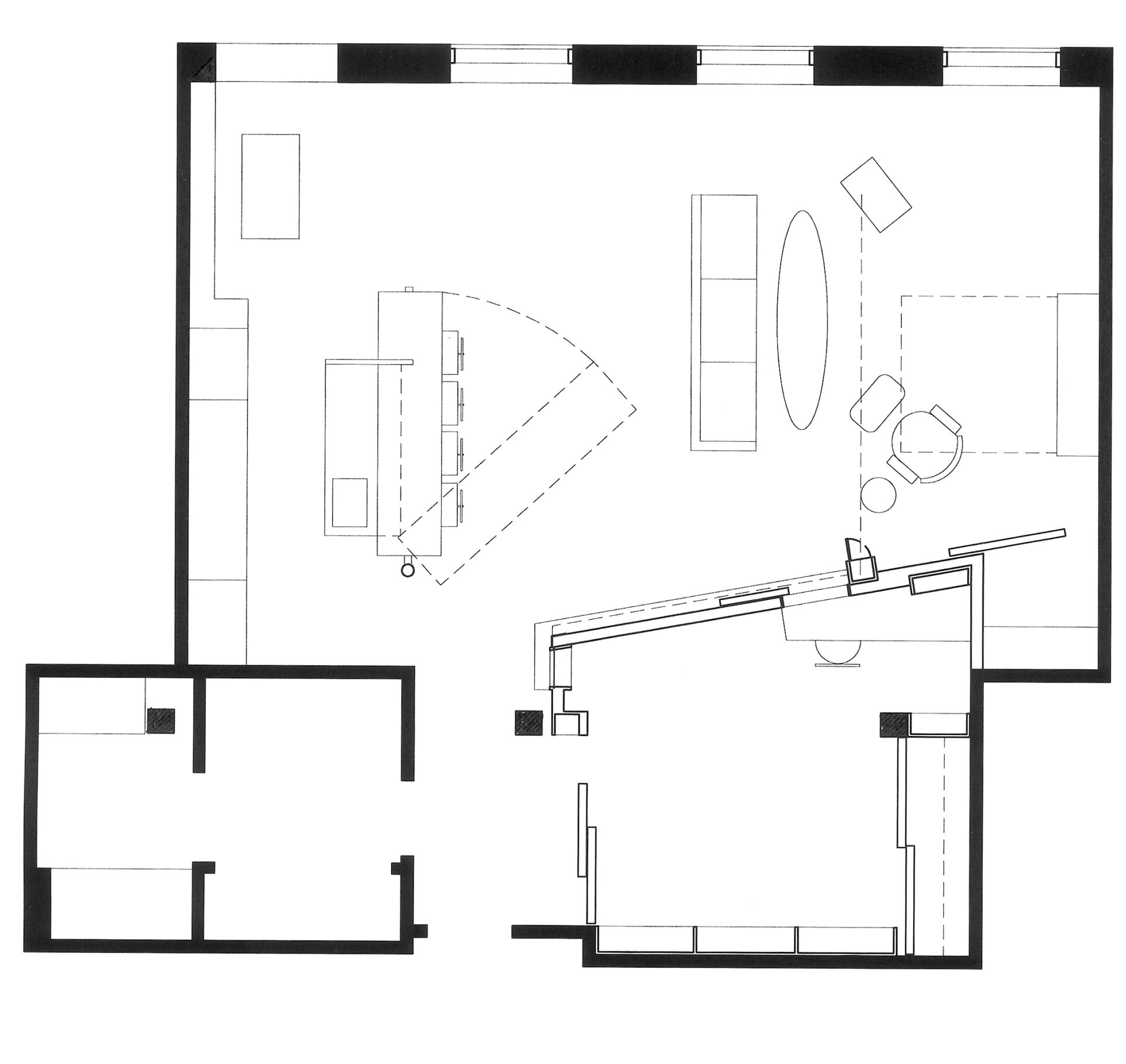

The architectural response, in a seeming inversion of Sullivan, is that function follows form – on hinges, casters, and tracks – about the space. A pivoting island rotates from compact meal prep mode to expansive dining table. Sliding shoji-esque screens enclose an office while allowing daylight deep into the space. A Murphy bed stands out-of-view within the living room then folds down at bedtime to signal the shift from studio to studio apartment. With an eye on budget, hardware is off-the-shelf and materials are inexpensive plywood, paint, and sheet metal. It is through their careful crafting, composition, and assembly that Brand is invalidated and form somehow transcends funding.

Satisfying both program and purse – if not precisely Sullivan and Brand’s maxims – our bachelor wins out in the functioning form of this loft.